#12. So Brut.

The Brutalist movement in relation to architecture and the controversy that came with.

I did a presentation a while ago on the brutalist movement in architecture after watching the Oscar-winning film, The Brutalist. A somber yet moving film that made me reflect on how the architect is often portrayed as the tragic hero. Sure, the title “architect” sounds like it’s all that but there are endless hoops of hardship to jump through. There is a sense of reward and accomplishment in the work but most architects hold themselves to incredibly high standards, often becoming their own toughest critics.

“The Brutalist is not a film about architecture—it’s a film of architecture, in its raw emotional force, unapologetic honesty, and unflinching ability to challenge its audience.” - Paul Petrunia

I enjoyed the film, it had me in the feels with all the juxtapositions of dark and doom, lightness, beauty and inspiration. Seeing the film was like seeing a dark thunderstorm at dusk in the summer, scary but so captivating and beautiful in a way that you can’t stop watching.

[on Brutalist architecture] “natural features that are so large, massive, and inherently dangerous that they put us in a state of awe-inspiring disbelief - and yet, and despite their mass and their danger, they give us feelings of deep pleasure and joy.” - Edmund Burke, philosopher

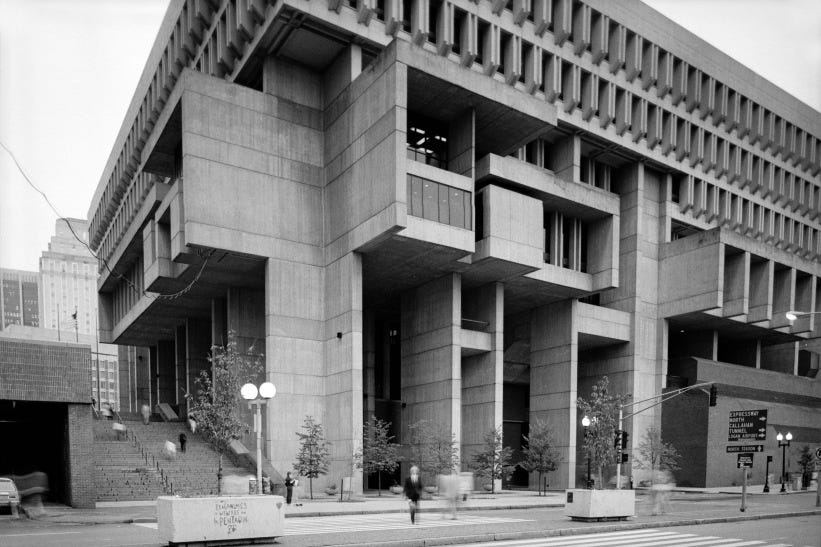

Brutalist architecture was developed Post-War in the 1950’s. It’s characterized by raw materials, typically exposed concrete — béton-brut, termed by Le Corbusier). Brutalist buildings present themselves as monolithic, utilitarian and are unapologetically honest by seeing the materials as they are. Brutalist architecture is bold and brings much controversy. Some view brutalist buildings as ugly, down-right bad and brutal (literally!)

I, however, am a fan of brutalist buildings. Circa 2014 when I was burning the midnight oil in Building 22 (the architecture building at Carleton University that breathes Brutalism), which made me appreciative of these modest and massive structures. I always felt safe and nurtured amongst the robust walls of concrete. Amazed that I could stare at the texture, the line patterns, the many shades of grey and dimension of the wall surface for a long period of time — a nice mental break from class. Perhaps because the architecture is stripped to its simplest form, it lets you focus on the essence of the structure without overwhelming the mind with the finishes, paint or cladding. It is what it is and there’s something truly spectacular about that.

After further research, I noticed a pattern; public and civic Brutalist buildings are often well-maintained and even celebrated, whereas residential and private buildings are frequently abandoned and left to deteriorate. I assume the reasons tie back to funding — too expensive to repair and too expensive to demolish. It’s a shame, especially because these were people’s homes.

Civic Brutalist Buildings

VS. Residential Brutalist Buildings

When someone asked me a while ago if there was a market for interior stylists and designers for the middle/lower class, this comparison of Brutalist architecture lit up in my brain. “Do people actually care? Will they spend money on this?” My immediate was response was, “Of course! Who wouldn’t want to spend some money to spruce up their home to make it the highest potential?! You can still make a space look great on a budget!” … But as the Brutalist movement has shown and especially with our economy these days, this may not be a priority. I also thought that maybe people just don’t care? Maybe they are content with how their place is and can’t envision what it could become. Or is it because they just aren’t aware of the possibilities… you don’t know what you don’t know.

These are some of the questions that have been on my mind lately and I’m curious to hear your thoughts (as well as your Rotten Tomatoes rating of The Brutalist)

Be well,

Caro